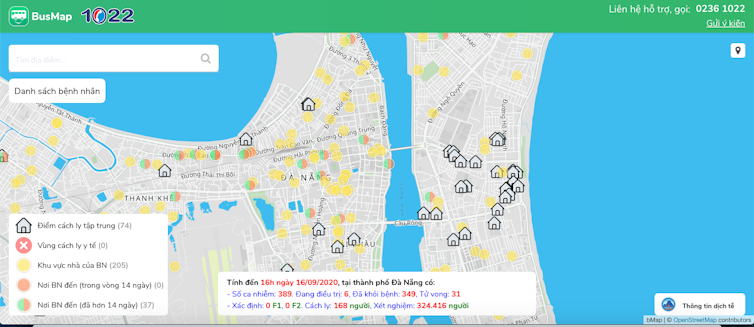

Smalley pulled out her cellphone, scrolling through a map app with hundreds of white pins. Each GPS marker pins the suspected location of a mule’s foot fern. A local conservationist spent weeks during the pandemic combing through satellite images and identifying the GPS coordinates of mule’s foot ferns on the mountain range.

Serene Smalley uses a machete to fell branches of the fern before injecting a small amount of pesticide into the base of the plant.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

To the untrained eye, a mule’s foot fern can look like a native plant, the hapuu fern. “The hapuu is very lacy and pretty,” she said, while the fond of the invasive fern is pointed. “Which reminds me of a snake.”

Some of the offending ferns are right off the Poamoho Ridge Trail near Wahiawa, but to reach others she will have to scale steep slopes in the rain. Smalley invested $60 in specialized shoes that look like hooves and have metal spikes embedded in the soles for traction. They were designed for fishermen and she uses duct tape to stabilize her ankles for the long hike ahead.

For six years Smalley has been scaling mountains, camping on remote peaks and navigating mudslides to kill thousands of non-native plants. She’s one of only about a dozen elite volunteers trusted by the state Department of Land and Natural Resources to assist in the dangerous task of eradicating invasive plants from the nearly 2.2 million acres of protected forests across the state.

“I can definitely see progress,” Smalley said. “It’s very, very rewarding.”

Watersheds provide clean drinking water, carbon sequestration and help prevent floods and droughts. A University of Hawaii study estimated the Koolau Range provides between $7.4 billion and $14 billion in value to the state.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

These volunteers, along with hundreds of state employees, dozens of environmental groups and an army of local hunters are fighting an uphill battle to protect Hawaii’s forests — and Hawaii’s drinking water.

The efforts involve coordinating a diverse group of stakeholders that don’t always see eye-to-eye, expensive land acquisitions, millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded fencing and excursions to some of the most remote areas of the island to remove invasive plants.

All this work is amid a backdrop of climate change, which the Honolulu Board of Water supply says is a top threat to drinking water security on the island.

More than 90% of Hawaii’s drinking water comes from aquifers: underground reservoirs of freshwater. Rising sea levels will make some freshwater aquifers turn brackish.

Hawaii’s population has almost doubled since statehood, and pre-pandemic the state was seeing a record number of visitors. But rainfall patterns have taken the opposite trajectory: decreasing at least 18% in the past 30 years, said state sustainability coordinator Danielle Bass.

Healthy forests could provide a one-two punch to the effects of climate change in Hawaii: sequestering carbon and allowing freshwater aquifers to recharge with rainfall.

“Without the necessary coordination and action, we risk a potential freshwater crisis for Hawaii’s future,” Bass said.

Use the search tool to find the watersheds where you live, work and play on Oahu. Yoohyun Jung/Civil Beat

This is where Hawaii’s native trees come in. Tall koa trees on the highest ridges absorb water from passing clouds and can trigger rainfall. Droplets land on shorter ohia trees, whose contours and thick bark are excellent at collecting water and injecting it into the ground.

Ohia trees have long held a special place in Native Hawaiian culture because they’re the first tree to grow on lava flows, their connection to the rain and the fabled love story of Ohia and Lehua.

Approximately half of all native trees on Hawaii’s six main islands are ohias.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

But this sacred tree is being killed by a fast-moving fungus, aptly titled rapid ohia death.

“The big concern with rapid ohia death is that it could wipe out the building blocks of our watersheds,” said Katie Ersbak, a watershed partnerships planner with the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

The two strains of fungi that cause the disease spread through the air and choke a tree’s ability to absorb water. When researchers identify a tree infected with the fungus, they chop it down and quarantine the area with plastic tarps to keep spores from spreading.

Hikers in Hawaii are being asked to do their part by scrubbing mud from their shoes and spraying gear with alcohol before and after excursions. Ersbak even has separate boots, clothing, camping gear and backpacks for every island to avoid spreading the fungi, which is now found on the Big Island, Maui, Kauai and Oahu.

And when an ohia tree dies, invasive species like strawberry guava are fast to move in.

“I don’t like to say that certain plants are bad, but we just want plants to be where they’re supposed to be,” Ersbak said.

Katie Ersback uses the naupaka flower to explain the importance of a healthy watershed from mauka to makai. The naupaka grows high in the mountains and along the shoreline. Its petals form a half-circle. When you put the two flowers together they form a complete circle.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

Each layer in a Native Hawaiian forest is specially evolved to coexist and sustain the ecosystem. Compared to the thick, rugged bark of the ohia, the invasive strawberry guava has very shiny, smooth bark. Water runs right off strawberry guava trees and onto the ground, not giving nearby plants enough time to absorb water and leading to erosion.

Strawberry guava is also fast-growing and monopolizes water to spur its growth. It’s a similar story with the mule’s foot fern Smalley has been working to eradicate. The fern is excellent at blocking light from small plants and mosses on the forest floor: eliminating an important element of the forest.

“These plants didn’t evolve for cooperation with the Hawaiian ecosystem,” Ersbak said. “They’re in competition, not harmony.”

On Oahu, more than 80% of the native forest has been eradicated. Now only the tallest peaks on the island are majority-native, but invasive species inch higher up the peaks every year.

Non-native plants are aided by cattle, goats, deer and pigs that roam through the forests.

Centuries ago Polynesians brought pigs to Hawaii, enriching diets and making pork an important part of Hawaiian culture and cuisine. But as more hooved animals like cows, goats and deer were introduced over the centuries, native animals and plants began to suffer. These hooved animals are excellent climbers and spread the seeds of non-native plants and weeds easily.

Hawaiian plants and animals evolved in isolation for millions of years and aren’t equipped with defenses against these grazers, but it wasn’t until the animals began threatening the economy that the government took action.

In the late 1800s, sugar plantation owners began noticing a decrease in water supply, and the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association lobbied for the creation of an agency to protect agricultural lands and forests. The territorial government created such an agency in 1903 and began building fences to keep grazers away from forests.

The government is still building fences 117 years later.

“It’s the best defense we have,” Ersbak said.

Building fences in remote sections of the forest is expensive. A recent 1,400-acre fence cost over a million dollars.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

Since 2013, DLNR has built 132 miles of fence, and now more than 140,000 acres of forests have steel wire zig-zagging through steep, muddy peaks.

But this plan is alienating a group of people integral to the protection of native forests: hunters.

“Fencing is definitely the biggest concern and discussion point among the hunters,” said Josiah Jury, a longtime hunter on Oahu and former watershed manager.

As a member of the Pig Hunters Association of Oahu, Jury spends a lot of time talking with hunters who he said feel left out of conversations about land management.

“They say these wild boars are such a big problem but there’s pushback to opening more areas to hunting,” he said.

Jury said some hunters may cut through a fence if it’s blocking access to an area they’ve hunted in for generations or if other areas are too crowded with hikers or other hunters.

“I’m not saying it’s right but we do have a lot of people who want to hunt and we’re providing a free service,” he said. “Hunting made me the man I am today and our next generation deserves the opportunity to have these powerful experiences.”

Tensions on state lands have led many hunters to start courting private landowners, and are part of the reason why the Pig Hunters of Oahu exists as a group: as a resource for landowners struggling with pig invasions. This helps the entire watershed because conservation doesn’t stop at a property line.

Watersheds aren’t just forests, they’re the entire area mauka to makai. It’s why many watershed lines run along ahupuaa boundaries. These traditional systems of land management were used by Native Hawaiians for centuries to balance the ecosystem and economy. Residents living in each ahupuaa would be directly impacted by land management decisions made upstream, and the entire community would suffer or thrive along with the ecosystem.

In 2020, groups managing forests, farmland, urban development, coastal resources and marine ecosystems each have their own priorities and processes.

“It takes an immense amount of coordination and cooperation between agencies and groups,” Erbank said. “We know that these plants and animals don’t care about property lines, we have to manage the entire landscape for effectiveness.”

To coordinate efforts and share resources, stakeholders have formed watershed management partnerships. The group overseeing the Koolau Mountain range has over 19 members.

Participation is voluntary and private landowners can either manage their watersheds themselves — consulting with other members for advice — or they can allow state employees and volunteers to build fences and remove invasive species while inviting hunters onto their land to manage feral pig populations.

Over 2 million acres of Hawaiian forests are managed by watershed partnerships, compromised of state agencies, conservation groups and private landowners. Yoohyun Jung/Civil Beat

Kamehameha Schools, the largest private landowner in the partnership, outsources the vast majority of its management while Kualoa Ranch has pivoted to actively restoring its land in recent years.

“Anything we do upstream affects everything below,” said Taylor Kellerman, the director of diversified agriculture and land stewardship at Kualoa Ranch in Kaneohe.

Taylor Kellerman’s next goal is to start growing sandalwood on the ranch.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

On a Monday morning Kellerman drove his truck over dips in the dirt roads that zig-zag across the three watersheds owned by Kualoa Ranch. The thousands of visitors to the ranch in Kaneohe may think that the gullies in the dirt road are for added excitement as their ATVs and tour jeeps bounce along, but they’re actually strategically placed to limit erosion, and the negative effects loose sediment can have on ocean ecosystems.

“We’re our own neighbors,” Kellerman said.

While Kualoa Ranch’s main economic driver is tourism, they are still a working ranch, raising cattle and pigs in the valley while farming oysters, shrimp and tilapia along the shoreline.

“Revenue from the visitors is used so we don’t have to succumb to financial pressure to develop the land,” he said.

In the five years Kellerman has worked at the ranch, the focus on restoring the forest has intensified, with the creation of an on-site conservation crew of 12 full-time employees and lots of experimenting.

Early efforts to restore native forests on the ranch were unsuccessful, because workers cleared an entire section down to the dirt and planted native trees. Invasive plants moved in and choked out the natives.

“Koa is like the gateway drug for reforestation.” – Taylor Kellerman, Kualoa Ranch

“We’re always learning,” he said. Now the ranch is trying to selectively remove invasive trees and immediately replant koa.

Driving around the Hakipuu watershed at Kualoa Ranch you’ll see dozens of round cages made of chicken wire. Kellerman calls them donuts, and uses the wire to protect koa saplings from cattle and feral pigs that roam the hills.

Taylor Kellerman’s conservation budget is tied to the ranch’s profits from agriculture, ranching and aquaculture.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

Kellerman’s friend and fellow watershed manager at Haleakala Ranch on Maui uses a similar design, and during a recent visit the two swapped “war stories” about cattle and pigs destroying their protection efforts. Both independently settled on the donut design to protect the koa saplings.

“Koa is like the gateway drug for reforestation, because it’s easy to obtain seed and they tend to do pretty well,” he said. “Ohia is the next one and they get a little harder as you go.”

For state lands and watersheds without a dedicated in-house conservation team, people like Ersbak with the Department of Land and Natural Resources must determine where to spend valuable resources.

In 2011 the state started designating priority watersheds for conservation. Some of the most threatened forests made the list, but so did forests that were in pretty good shape and could realistically be restored.

Completely native forests are only found in the most remote areas of the island. Most hiking trails lead through a mix of native and invasive plants.

Kuʻu Kauanoe/Civil Beat

It’s why Smalley ignores strawberry guava along the lower section of the Poamoho Ridge Trail. There are too many strawberry guava trees to ever fully eradicate the species on Oahu, while conservationists still have an edge on the mule’s foot fern in the higher reaches of the mountain.

“It really is hard to know that you won’t be able to get them all,” Smalley said. “It is so time and effort-intensive it’s great to know that where I’m putting that effort in really counts.”

But if the sole goal of the watershed partnership is to recharge aquifers, then focusing resources solely on native plants may not be the most efficient route, said Victoria Keener, a climate researcher and member of the Honolulu Climate Change Commission.

“For years the saying was: if we build up native forests, the rain will follow. But that was really done without a lot of science to back it up,” she said. “And so when everyone started doing the science to back it up, the picture became a lot more complicated.”

In 2011 then-Governor Neil Abercrombie launched “The Rain Follows the Forest,” a massive conservation effort named after a traditional Hawaiian proverb. The goal was to double the amount of protected watershed area in 10 years.

Five years in, a report to the Legislature showed the project had removed invasive species and built fences to protect about 133,000 acres of priority watershed across the state. That initiative was replaced in 2015 by Gov. David Ige’s goal to protect 30% of the state’s priority watersheds, about 253,000 acres, by the year 2030. With 10 years left to meet the goal, 55% of the earmarked watersheds are under high-level protection.

An ongoing research project at the University of Hawaii is now working to determine how specific plants affect aquifer recharge. Preliminary findings indicate that some native grasses consume more water than other non-native grasses and have different impacts on sediment runoff.

“It gets really complicated,” Keener said. “We need science to direct these decisions.”

When large-scale forest conservation first began in Hawaii at the turn of the 20th century, well-meaning residents were planting fast-growing trees like eucalyptus to stop erosion. At the peak of reforestation in the 1930s, nearly 2 million trees were planted a year in Hawaii, and scientists are just beginning to fully understand the detrimental impacts these new species had on the entire ecosystem.

“We really need to work carefully and deliberately and it’s not lost on me that decisions we make can have really big impacts,” Ersbak said. “Conservation is a game of managing unexpected consequences.”

Mauka to Makai

Drag your cursor around the 360° video to see how forests impact shorelines.

This story is part of the Pulitzer Center’s nationwide Connected Coastlines reporting initiative.