by Omar Suleiman, Al Jazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/2/21/malcolm-x-is-still-misunderstood-and-misused

Image: Al Jazeera

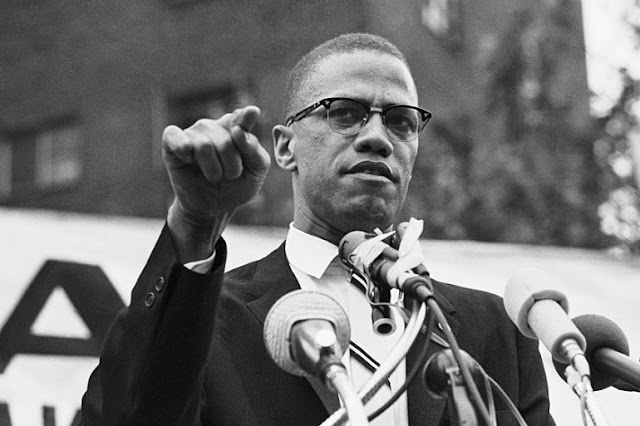

Every semester in which I teach a course on Muslims in the Civil Rights Movement at Southern Methodist University, I give my students a selection of quotes from both Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X and ask them to guess who said what. So for example, I will posit the following two quotes and ask for their proper ascription:

“Ignorance of each other is what has made unity impossible in the past. Therefore, we need enlightenment. We need more light about each other. Light creates understanding, understanding creates love, love creates patience, and patience creates unity. Once we have more knowledge (light) about each other, we will stop condemning each other and a United front will be brought about.”

“The majority of white Americans consider themselves sincerely committed to justice for the Negro. They believe that American society is essentially hospitable to fair play and to steady growth toward a middle-class Utopia embodying racial harmony. But unfortunately this is a fantasy of self-deception and comfortable vanity.”

And every single time, they have been unable to identify the first quote as belonging to Malcolm, and the second to Martin. But it is not just a few students that have gotten it wrong. The American education system and most mainstream portrayals of Martin and Malcolm have been simplistic and sanitising.

Martin is the perfect hero who preached non-violence and love, and Malcolm the perfect villain who served as his violent counterpart, preaching hate and militancy. The result is not just a dishonest reading of history, but a dichotomy that allows for Dr King to be curated to make us more comfortable, and Malcolm X to be demonised as a demagogue from whom we must all flee. Reducing these men to such simplistic symbols allows us to filter political programmes according to how “King-like” they are. Hence, illegitimate forms of reconciliation are legitimised through King and legitimate forms of resistance are delegitimised through Malcolm X.

Malcolm was never violent, not as a member of the Nation of Islam, nor as a Sunni Muslim. But Malcolm did find it hypocritical to demand that black people in the United States commit to non-violence when they were perpetually on the receiving end of state violence. He believed that black people in the US had a right to defend themselves, and charged that the US was inconsistent in referencing its founding fathers’ defence of liberty for everyone but them.

Malcolm knew that his insistence on this principle would cause him to be demonised even further and ultimately benefit the movement of Dr King, which is exactly what he had intended. Just weeks before his assassination, he went to Selma to support Dr King and willingly embraced his role as the scary alternative. In every interview, in his meeting with Dr Coretta Scott King, and elsewhere, he vocalised that the US would do well to give the good reverend what he was asking for, or else.

But he never actually said what the “or else” was, placing a greater urgency on America to cede to King’s demands. Malcolm had no problem playing the villain, so long as it led to his people no longer being treated like animals. And while King may have been steadfast in his commitment to non-violence, the thrust of Malcolm fully served its purpose.

As Colin Morris, the author of Unyoung, Uncolored, Unpoor wrote, “I am not denying passive resistance its due place in the freedom struggle, or belittling the contribution to it of men like Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Both have a secure place in history. I merely want to show that however much the disciples of passive resistance detest violence, they are politically impotent without it. American Negroes needed both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X …”.

But it was not just that Malcolm and Martin had complementary strategies to achieve black freedom, they also spoke to different realities. Malcolm spoke more to the Northern reality of black Americans who were only superficially integrated, whereas Martin spoke to the Southern reality where even that was not possible.

Malcolm also spoke to the internalised racism of black people that was essential to overcome for true liberation. As the late James Cone states, “King was a political revolutionary. Malcolm was a cultural revolutionary. Malcolm changed how black people thought about themselves. Before Malcolm came along, we were all Negroes. After Malcolm, he helped us become black.”

That is why, despite the diminishing of Malcolm in textbooks and holidays, he has been consistently revived through protest movements and the arts. He has lived through the activism of the likes of Muhammad Ali and Colin Kaepernick, inspired the black power movement, and been an icon for American Muslims on how to exist with dignity and faith in a hostile environment.

And even in those claims to Malcolm as a symbol, Malcolm himself in the fullness of his identity is erased. In championing his movement’s philosophy, some seek to secularise him, intentionally erasing his Muslim identity. And in championing his religious identity, others seek to depoliticise him. This was a tension that Malcolm noted in his own life, saying: “For the Muslims, I’m too worldly. For other groups, I’m too religious. For militants, I’m too moderate, for moderates I’m too militant. I feel like I’m on a tightrope.”

Muslims too should be cautious not to sanitise Malcolm, as the US has sanitised Dr King. To restrict Malcolm solely to his Hajj experience is similar to restricting King solely to his “I have a dream” speech. Malcolm was a proud Muslim who never stopped being black. And while he no longer subscribed to a condemnation of the entire white race, he was unrelenting in his critique of global white supremacy.

Malcolm was consistently growing in a way that allowed him to not only champion his own people’s plight more effectively but to tackle a broader set of interconnected issues. And while history seems to posit Malcolm as his polar opposite, Dr King had begun to articulate many of the same positions that made Malcolm so unpopular.

In the words of the great James Baldwin, “As concerns Malcolm and Martin, I watched two men, coming from unimaginably different backgrounds, whose positions, originally, were poles apart, driven closer and closer together. By the time each died, their positions had become virtually the same position. It can be said, indeed, that Martin picked up Malcolm’s burden, articulated the vision which Malcolm had begun to see, and for which he paid with his life. And that Malcolm was one of the people Martin saw on the mountaintop.”

Perhaps it is time we ask why we only seem to celebrate one of them.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect Al Jazeera’s editorial stance.