by Ellen Corrick, John Hellstrom, and Russell Drysdale, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/we-pieced-together-the-most-precise-records-of-major-climate-events-from-thousands-of-years-ago-heres-what-we-found-144575

Between 115,000 and 11,700 years ago, the Earth would have been almost unrecognisable. Massive ice-sheets covered northern Europe and northern Asia, and about half of North America, and global sea-levels were as much as 130 meters lower than today.

In this period, known as the “last glacial period”, the climate was much cooler and drier than today. It was punctuated by some of the largest and most rapid climate change events in Earth’s recent geological history.

For a long time, scientists have pondered how closely timed these abrupt climate change events were between Greenland and other regions of the world — far beyond the Arctic.

In our research, published today in Science, we’ve shown abrupt climate changes across the Northern Hemisphere and into the southern mid-latitudes occurred simultaneously, within decades of each other, throughout the last glacial period. We’ve also determined exactly when the abrupt changes occurred, much more precisely than before.

This can help us predict how abrupt climate changes might play out in the future.

A series of abrupt climate changes

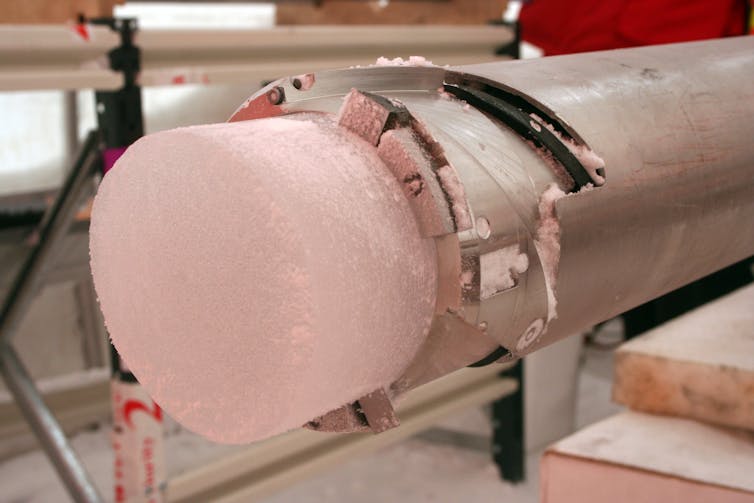

Scientists can peer into Earth’s climate history through long ice cylinders, called “ice cores”, drilled from the Greenland ice sheet. Changes in the chemical composition of these ice cores reveal that the surrounding atmospheric temperature repeatedly warmed by 8-16℃, and each time within just a few decades.

Each warming event was followed by a more gradual period of cooling. These abrupt warming and cooling events happened more than 25 times throughout the last glacial period, and are known as Dansgaard-Oeschger events. They reflect changes in circulation patterns of the Atlantic Ocean.

While we have records of climate changes from many regions, the relative timing of these changes between Greenland and across the northern hemisphere into the southern sub-tropics is not well understood.

This has been difficult to resolve because we need very precisely dated records to make exact comparisons in timing. Ice cores provide a wealth of information about Dansgaard-Oeschger events. But while they faithfully reproduce the patterns of past climate, they are difficult to date very precisely.

Crystal time capsules beneath our feet

For our study, we turned to more precisely datable climate records: those from cave stalagmites.

Stalagmites are cave mineral deposits, which build up layer-by-layer on the cave floor. Their growth is fed by water dripping from the cave ceiling, which carries with it a chemical signal of temperature and rainfall conditions above the cave at that time. This signal is trapped in the crystal structure of the growing stalagmite.

Stalagmites can be dated very precisely, by measuring the decay of minute amounts of uranium trapped in them. This key feature enables us to compare the timing of climate events from place to place.

However, long, high-quality stalagmite records are rare. Scientists from around the world have been working for more than 20 years to produce these records. Only now that enough records are available, we are able to make precise comparisons of the timing of Dansgaard-Oeschger events between different regions.

We collated and compared 63 published stalagmite records from caves in Asia, Europe and South America, and we determined the timings of abrupt climate changes in each.

What we found

Our results show that during each Dansgaard-Oeschger event, climate changes felt in Asia, South America and Europe occurred within decades of one another. Being able to determine this level of synchrony is remarkable, given we are looking at events that occurred many tens of thousands of years ago.

This means that as large temperature increases were occurring in Greenland, abrupt changes were also occurring in air temperature and rainfall in Europe, and in the monsoon systems in Asia and South America.

So why is this important? First of all, finding that climate change events occurred in lots of different parts of the world within decades provides clues as to how they started in the first place.

It tells us the changes were likely propagated from the North Atlantic region to these locations through the re-organisation of patterns in atmospheric circulation. And knowing this can help scientists narrow down the underlying triggers, which are still not conclusive.

And our findings mean the precise ages from the stalagmites can be used to better date ice cores, enhancing one of the most important records we have of the last glacial climate.

Implications for the future

The abrupt climate changes we studied occurred under very different conditions compared to the climate of today.

While our ancestors lived through the last glacial period, humans are unlikely to experience Dansgaard-Oeschger events for many thousands of years, until the earth has again cooled to glacial temperatures.

However, piecing together the puzzle of how abrupt climate changes took place in the past will help us to understand how abrupt climate changes might occur in the future. For example, our findings will help validate climate models used to predict climate changes.

Showing that profound changes in climate can occur simultaneously across large regions of the Earth highlights just how unstable and interconnected our climate system can be.