|

| Katta O'Donnell bringing class action lawsuit against Aust government. M Townsend |

by Jacqueline Peel and Rebekkah Markey-Towler, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/a-wake-up-call-why-this-student-is-suing-the-government-over-the-financial-risks-of-climate-change-143359

As the world warms, the value of “safe” investments might be at risk from inadequate climate change policies. This prospect is raised by a world-first climate change case, filed in the federal court last week.

Katta O’Donnell – a 23-year-old law student from Melbourne – is suing the Australian government for failing to disclose climate change risks to investors in Australia’s sovereign bonds.

Sovereign bonds involve loans of money from investors to governments for a set period at a fixed interest rate. They’re usually thought to be the safest form of investment. For example, many Australians are invested in sovereign bonds through their superannuation funds.

But as climate change presents major risks to our economy as well as the environment, O'Donnell’s claim is a wake-up call to the government that it can no longer bury its head in the sand when it comes to this vulnerability.

O’Donnell argues Australia’s poor climate policies – ranked among the lowest in the industrialised world – put the economy at risk from climate change. She says climate-related risks should be properly disclosed in information documents to sovereign bond investors.

O'Donnell’s arguments

O'Donnell’s claim alleges that by failing to disclose this information, the federal government breaches its legal duty. It alleges the government has engaged in misleading and deceptive conduct, and government officials breached their duty of care and diligence.

This is a standard similar to that owed by Australian company directors. Analysis from leading barristers indicates that directors who fail to consider climate risks could be found liable for breaching their duty of care and diligence.

O'Donnell argues government officials providing information to investors in sovereign bonds should meet the same benchmark.

Climate change as a financial risk

Under climate change, the world is already experiencing physical impacts, such as intense droughts and unprecedented bushfires. But we’re also experiencing “transition impacts” from steps countries take to prevent further warming, such as transitioning away from coal.

Combined, these impacts of climate change create financial risks. For example, by damaging property, assets and operations, or by reducing demand for fossil fuels with the risk coal mines and reserves become stranded assets.

This thinking is becoming mainstream among Australian economists. As the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s Geoff Summerhayes put it:

When a central bank, a prudential regulator and a conduct regulator, with barely a hipster beard or hemp shirt between them, start warning that climate change is a financial risk, it’s clear that position is now orthodox economic thinking.

Why safe investments are under threat

Sovereign bonds are a long-term investment. Katta O’Donnell’s bonds, for example, will mature in 2050. These time-frames dovetail with scientific projections about when the world will see severe impacts and costs from climate change.

And climate change is likely to hit Australia particularly hard. We’ve seen the beginning of this in the summer’s ferocious bushfires, which cost the economy more than A$100 billion.

Over time, climate risks may impact sovereign bonds and affect Australia’s financial position in a number of ways. For example, by impacting GDP when the productive capacity of the economy is reduced by severe fires or floods.

Frequent climate-related disasters could also hit foreign exchange rates, causing fluctuations of the Australian dollar, as well as putting Australia’s AAA credit rating at risk. These risks would reduce if the government took climate change more seriously.

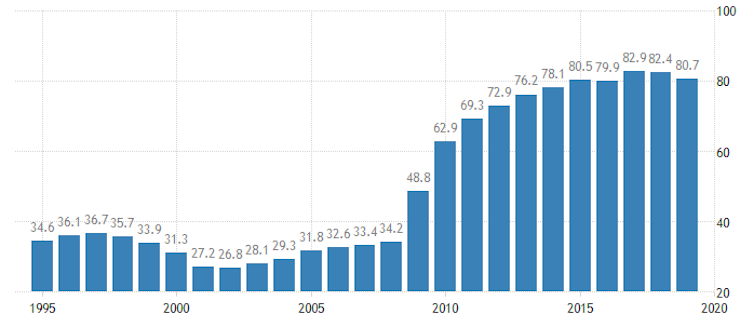

Already, some investors are voting with their feet. Last November, Sweden’s central bank announced it had sold Western Australian and Queensland bonds, stating Australia is “not known for good climate work”.

Unprecedented, but not novel

O’Donnell’s case against the federal government is an unprecedented climate case, even if its arguments are not novel.

Australia has been a “hotspot” for climate litigation in recent years, but the O'Donnell case is the first to sue the Australian government in an Australian court.

Previous cases suing governments have often raised human rights, such as the high-profile Urgenda case in 2015 against the Dutch government – the first case in the world establishing governments owe their citizens a legal duty to prevent climate change.

The O'Donnell case is also unique in its focus on sovereign bonds. But cases alleging misleading climate-related disclosures are themselves not new.

In Australia, shareholders sued the Commonwealth Bank of Australia in 2017 for failing to disclose climate change-related risks in its 2016 annual report. The case was settled after the bank agreed to improve disclosures in subsequent reports.

In another headline-making case, 23-year-old council worker Mark McVeigh is taking his superannuation fund, Retail Employees Superannuation Trust, to court seeking similar disclosures.

The O'Donnell case builds on this line of precedent, extending it to disclosures in bond information documents. As such, courts will likely take it seriously.

What precedent might it set?

If the O'Donnell case is successful it could establish the need for disclosure of climate-related financial risks for a range of investments.

At a minimum, a ruling in O'Donnell’s favour may compel the Australian government to disclose climate-related risks in its information documents for investors. This might make people think twice about how they choose to invest their money, especially as investors seek to “green” their portfolios.

It could also give rise to litigation using the same legal theory in sovereign bond disclosure claims against other governments, much in the way that the Urgenda case has spawned copycat proceedings from Belgium to Canada.

Whether the case provides the impetus for further government action to improve the effectiveness of Australia’s climate policies remains to be seen.

Still, it’s clear climate-related financial risks have entered the corporate boardroom. With this case, they’ve now come knocking at the government’s door.