by John Whittaker, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/modern-monetary-theory-the-rise-of-economists-who-say-huge-government-debt-is-not-a-problem-141495

There is no limit to the quantity of money that can be created by a central bank such as the Bank of England. It was different in the days of the gold standard, when central banks were restrained by a promise to redeem their money for gold on demand. But countries moved away from this system in the early part of the 20th century, and central banks nowadays can issue as much money as they like.

This observation is the root of modern monetary theory (MMT), which has attracted new attention during the pandemic, as governments around the world increase spending and public debts become all the more burdensome.

MMT proponents argue that governments can spend as necessary on all desirable causes – reducing unemployment, green energy, better healthcare and education – without worrying about paying for it with higher taxes or increased borrowing. Instead, they can pay using new money from their central bank. The only limit, according to this view, is if inflation starts to rise, in which case the solution is to increase taxes.

MMT’s roots

The ideas behind MMT were mainly developed in the 1970s, notably by Warren Mosler, an American investment fund manager, who is also credited with doing much to popularise it. However, there are many threads that can be traced further back, for instance to an early 20th-century group called the chartalists, who were interested in explaining why currencies had value.

These days, prominent supporters of MMT include L Randall Wray, who teaches regular courses on the theory at Bard college in Hudson, New York state. Another academic, Stephanie Kelton, has gained the ear of politicians such as Bernie Sanders and, more recently, Democrat US presidential candidate Joe Biden, providing theoretical justification for expanding government spending.

There are more strands to MMT besides the idea that governments don’t need to worry overly about spending. For instance, supporters advocate job guarantees, where the state creates jobs for unemployed people. They also argue that the purpose of taxation is not, as mainstream economics would have it, to pay for government spending, but to give people a purpose for using money: they have to use it to pay their tax.

But if we overlook these points, the main policy implication of MMT is not so controversial. It is not too far from the current new-Keynesian orthodoxy which advises that if there is unemployment, this can be cured by stimulating the economy – either through monetary policy, which focuses on cutting interest rates; or through the fiscal policies of lower taxes and higher spending.

Against this position is the monetarist doctrine that inflation is caused by too much money, and the common belief that too much government debt is bad. These two principles explain why central banks are strongly focused on inflation targets (2% in the UK), while the aversion to debt in the UK and elsewhere was the driving force behind the “austerity” policy of cutting government spending to reduce the deficit – at least until the coronavirus pandemic made governments change direction.

The crux

So, who is right – the MMT school or the fiscal and monetary conservatives? In particular, is it sensible to pay for government spending with central bank money?

When a government spends more than it receives in taxation, it has to borrow, which it usually does by selling bonds to private sector investors such as pension funds and insurance companies. Yet since 2009, the central banks of the UK, US the eurozone, Japan and other countries have been buying large amounts of these bonds from the private-sector holders, paying for their purchases with newly created money. The purpose of this so-called “quantitative easing” (QE) has been to stimulate economic activity and to prevent deflation, and it has been greatly expanded in response to the pandemic.

At present in the UK, over £600 billion or 30% of government debt is effectively financed by central bank money – this is the value of government bonds now held by the Bank of England as a result of QE. There are similar high proportions in the other countries that have been undertaking QE.

Despite all this creation of new central bank money and the large increase in government debt in the UK and other large economies since the financial crisis of 2007-09, nowhere has there been a problem with inflation. Indeed, Japan has struggled for three decades to raise its inflation rate above zero. This evidence – that neither large debt nor large money creation has caused inflation – seems to vindicate the MMT policy recommendation to spend.

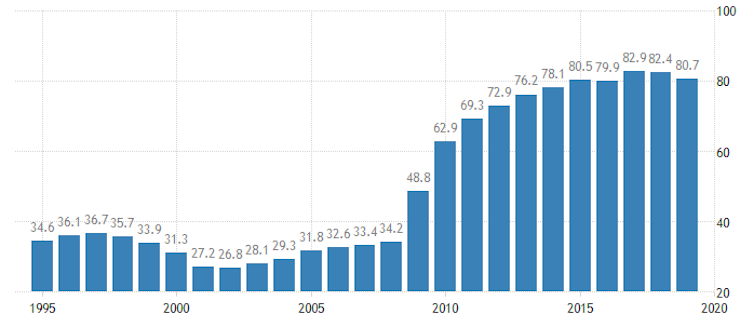

UK public debt as a % GDP

Of course, there are many counterexamples in which these conditions have been associated with hyperinflation, such as Argentina in 1989, Russia at the breakup of the Soviet Union, and more recently Zimbabwe and Venezuela. But in all these cases there was an assortment of additional problems such as government corruption or instability, a history of defaults on government debt, and an inability to borrow in the country’s own currency. Thankfully, the UK does not suffer from these problems.

Since the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, UK government spending has been rapidly increasing. Debt is now about £2 trillion or 100% of GDP. And the Bank of England, under its latest QE programme, has been buying up UK government bonds almost as fast as the government is issuing it.

Thus the crucial question is: will inflation remain subdued? Or will this vast new increase in QE-financed government spending finally cause inflation to take off, as the easing of lockdown releases pent-up demand?

If there is inflation, the Bank of England’s task will be to choke it off by raising interest rates, and/or reversing QE. Or the government could try out the MMT proposal to stifle the inflation with higher taxes. The trouble is that all these responses will also depress economic activity. In such circumstances, the MMT doctrine of free spending will not look so attractive after all.