by Denis Muller, The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/media-have-helped-create-a-crisis-of-democracy-now-they-must-play-a-vital-role-in-its-revival-139653

In May 2020, with the world still in the grip of the coronavirus pandemic, Margaret MacMillan, an historian at the University of Toronto, wrote an essay in The Economist about the possibilities for life after the pandemic had passed.

On a scale of one to ten, where one was utter despair and ten was cautious hopefulness, it would have rated about six. Her thesis was that the future will be decided by a fundamental choice between reform and calamity.

She saw the world as being at a turning point in history. It had arrived there as a result of the conjunction of two forces: growing unrest at economic inequality, and the crisis induced by the pandemic.

It was at such times, she argued, that societies took stock and were open to change. Such a time, for example, was in the immediate aftermath of the second world war, which resulted in radical reforms to international political and economic frameworks.

She was writing against a backdrop of a larger crisis – the crisis in democracy. The most spectacular symptoms of this were the election of Donald Trump as president of the United States and the Brexit referendum. Both occurred in 2016, and both appealed to populism largely based on issues of race and immigration.

In the four years since, many books have been written on this crisis, among them Cass Sunstein’s #republic, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt’s How Democracies Die, and A. C. Grayling’s Democracy and its Crisis.

Then, somewhat surprisingly, in May 2020 a new spirit of what might be called “economic morality” announced itself.

This came from within the Republican Party of the United States. It happened while Trump, that most amoral of Republican presidents, was in office, and reasserted some of the fundamental values of conservatism.

It took the form of a new organisation, American Compass, https://americancompass.org/, founded by Oren Cass, who was domestic policy adviser to Mitt Romney’s 2008 and 2012 US presidential election campaigns. He is also the author of an acclaimed book on labour markets, The Once and Future Worker: A Vision for the Renewal of Work in America.

American Compass’s mission, as stated on its website, was to:

… restore an economic consensus that emphasises the importance of family, community, and industry to the nation’s liberty and prosperity.

As the coronavirus pandemic wreaked havoc across the United States, Cass described the nation’s response as an indictment of what he called an “economic piety” – a form of ideological purity – that ignored many values that markets do not take into their calculations.

These included the well-being of workers, the security of supply chains, and the running down of America’s self-sufficiency, exemplified by a shortage of medical supplies.

His line of argument was supported by a senior Republican, Senator Marco Rubio, in an article for The New York Times. Rubio’s critique of the failure of American economic policy over two decades was crystallised in one sentence:

Why didn’t we have enough N95 masks or ventilators on hand for a pandemic? Because buffer stocks don’t maximize financial return, and there was no shareholder reward for protecting against risk.

The fact that this significant shift in economic thinking and socio-political priorities was coming out of elements in the Republican Party in the lead-up to the presidential election is perhaps an indication that MacMillan’s thesis has some substance. Perhaps democracies are on the cusp of a change in direction.

How the pandemic contracted the media landscape further

Alongside these developments, the existential crisis facing news media was made worse by the coronavirus pandemic. As business activity was brought to a stop by the lockdown, the need for advertising was drastically reduced.

Coming on top of the haemorrhaging of advertising revenue to social media over the previous 15 years, this proved fatal to some newspapers.

In Australia, the impact of this was worst in regional and rural areas. News Corp announced in May that more than 100 of its regional newspapers would become digital-only or close entirely.

In April, Australia’s largest regional newspaper publisher, Australian Community Media (ACM), announced it was suspending the printing of newspapers at four of its printing sites, halting the production of most of its non-daily local newspapers. ACM has about 160 titles.

These developments represented a serious loss to local communities and added to the democratic deficit already apparent over more than a decade as advertising revenue flowed away from traditional media to the global social media platforms.

Defending against the digital onslaught

At a national level, the Australian government took up a recommendation by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission to force the global platforms, particularly Facebook and Google, to pay for the news it took from Australian media.

The platforms mounted a fierce rearguard action against this proposal, which remains unresolved for now.

If a democratic revival is to occur, however, a strong media will be a necessary part of it. The necessity of a free press has been clear since the germination of modern democracy in the late 17th century, and in the late 18th century it was given powerful recognition in both legal and political terms.

In 1791 it was articulated in the First Amendment to the US Bill of Rights. In 1795, Edmund Burke stood up in the British House of Commons and asserted that the press had become what he called “the fourth estate of the Realm”.

If the media are to play their part in any democratic revival, however, financial and material security will be only a part of what is required.

One factor that has contributed to the present crisis in democracy is polarisation, the opening up of deep divisions between the main political parties of mature democracies. This has been magnified by media partisanship.

There is a lot of research evidence for this. One of the most significant is a 2017 study that showed the link in the United States between people’s television viewing habits and their political affiliations.

A further factor in the crisis has been the emergence of the “fake news” phenomenon. In the resultant swirling mass of information, misinformation and disinformation that constitutes the digital communications universe, people have returned to traditional mass media in the hope that they can trust what they see and hear there.

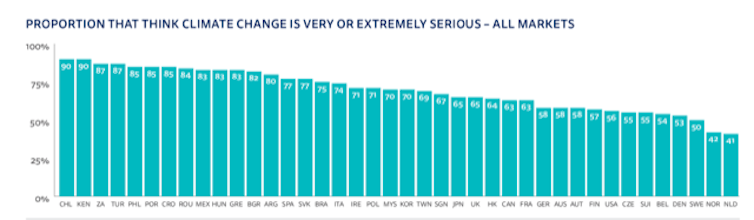

The Edelman Trust Barometer, an annual global study of public attitudes of trust towards a variety of institutions, including the media, showed that since 2015, public trust in the traditional media as a source of news had increased, and their trust in social media as a source of news had decreased.

Populism and scapegoating

A third factor in the crisis, exacerbated by the first two, is the rise of populism. Its defining characteristics are distrust of elites, negative stereotyping, the creation of a hated “other”, and scapegoating. The hated “other” has usually been defined in terms of race, colour, ethnicity, nationality, religion or some combination of them.

Powerful elements of the news media, most notably Fox News in the United States, Sky News in Australia and the Murdoch tabloids in Britain, have exploited and promoted populist sentiment.

This sentiment is reckoned to have played a significant part in the election of Trump.

It is also considered to have played a part in the outcome of the Brexit referendum.

It follows that if these are contributing factors to the crisis in democracy, then the media has a part in any democratic revival.

To do so, it needs to take four major steps. One is to focus resources on what is called public interest journalism: the reporting of parliament, the executive government, courts, and powerful institutions in which the public places its trust, such as major corporations and political parties. This work needs to include a substantial investigative component.

A second is to recommit to the professional ethical requirements of accuracy, fairness, truth-telling, impartiality, and respect for persons.

The third is to take political partisanship out of news coverage. Media outlets are absolutely entitled to be partisan in their opinions, but when it taints the news coverage, the public trust is betrayed.

The fourth is to recalibrate the relationship between professional mass media and social media.

That recalibration involves taking a far more critical approach to social media content than has commonly been the case until now.

While it is true the early practices of simply regurgitating stuff from social media have largely been abandoned, social media still exerts a disproportionate influence on news values. Just because something goes viral on social media doesn’t make it news unless it concerns a matter of substance.

Social media is where fake news flourishes, so the filter applied by professional mass media to what appears there needs to be strong and close-meshed.

That is the negative side of the recalibration.

The positive side is to further develop the extraordinary symbiosis that has been shown to exist between social and professional mass media.

It was most spectacularly demonstrated by the Black Lives Matter protests that followed the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis.

Social media allowed millions of people all over the world to be eyewitnesses to this gross act of police brutality.

Professional mass media, by applying its standards of verification and corroboration then disseminating the footage on its mass platforms, ensured the killing became known to the community at large, well beyond the confines of echo chambers and filter bubbles.

It also added that element of long-established public trust that respected news brands have to offer.

The world saw how powerful that combination was. A single act of police violence with racist overtones in a relatively obscure American city set off protests not just in the United States but in many countries with a history of police brutality against people of colour: Canada, Britain, Belgium, France, Australia, the Dominican Republic.

And then the same combination exerted a high level of accountability on the police for their further acts of violence against the protesters, which spilled over into police violence against the media covering those protests.

These events show the importance of the community having a common bedrock of reliable information on which to base a common conversation and a common response to an issue of common concern. It is the opposite of the fragmentation that is created by online echo chambers.

If Margaret MacMillan is right, and the world really is at a point where significant economic, political and social change is possible, let’s hope the media might be brave and honest enough to reflect on the contribution they have made to the creation of democracy’s crisis, and be prepared to change in order to help rebuild public trust in democratic institutions.